272: Jim Crow for All

Understanding The Trump Confederacy

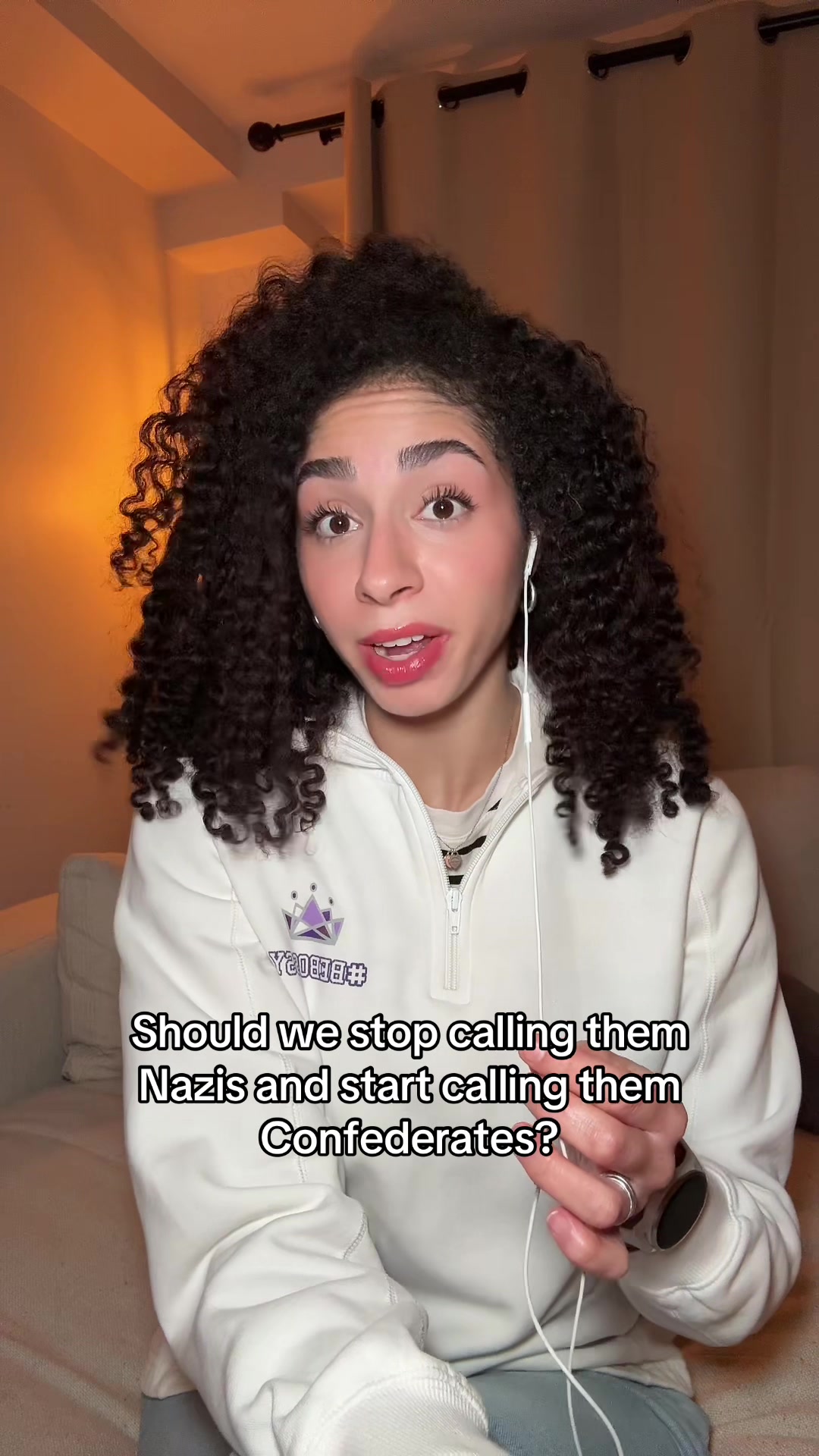

The language people reach for in moments of political rupture matters. It shapes what we notice, what we miss, and how we imagine resistance. Right now, contemporary American politics is routinely explained through the vocabulary of 1930s Germany. The comparison is understandable: mass rallies, media spectacle, charismatic demagogues, and the normalization of cruelty. Yet the deeper continuity runs elsewhere. The present moment aligns more coherently with the unresolved legacy of slavery and the unfinished business of the U.S. Civil War.

The American state did not stumble into authoritarianism from nowhere. It carried forward an internal enemy, an internal colony, and an internal economy of domination. Slavery was not only a labour system; it was a governing technology. It fused law, property, religion, violence, and infrastructure into a coherent order. When formal slavery ended, that order was re-engineered.

Reconstruction was abandoned. The Confederacy was defeated militarily but preserved culturally, economically, and legally. Jim Crow was not a betrayal of American democracy; it was one of its operating modes. Segregation, voter suppression, racial terror, and carceral control were mechanisms for maintaining a racialized labor regime in an industrializing economy. That regime never stopped evolving.

This is why contemporary enforcement institutions are better understood through that lineage. ICE functions less like a foreign secret police and more like modernized slave patrols. Their mandate is population control: deciding who belongs, who can move, who can work, and who can be disappeared into detention. The analogy to the Gestapo captures fear and brutality, but it obscures continuity. The American system did not import repression; it refined it.

The prison and policing apparatus tells the same story. Law enforcement in the United States grew directly out of slave-catching and strike-breaking. The contemporary prison-industrial complex preserves forced labor, legal disenfranchisement, and social death under a different name. This is a stable institutional inheritance.

The Civil War, in this sense, never ended. It was frozen, deferred, and partially laundered through constitutional amendments and market integration. Today, the ideological descendants of the Confederacy hold disproportionate power across state governments, courts, media ecosystems, and paramilitary networks. Their project has always been explicit: restore a racial hierarchy justified by Christianity, enforced by law, and protected by violence. Christian nationalism is the religious arm of an older political economy.

Why, then, does the 1930s analogy persist? Partly because of media. The rise of radio helped consolidate mass politics in Europe; social media now performs a similar function globally. Attention is centralized, emotions are amplified, and legitimacy is manufactured at scale. That parallel is real. But it is incomplete.

The 1860s metaphor captures something else that is equally decisive: industrial transformation. The original Civil War unfolded alongside the rise of industrial capitalism, railroads, mechanized agriculture, and national markets. The conflict was as much about economic systems as moral ones. Today’s moment mirrors that convergence. Artificial intelligence, automation, platform monopolies, and data extraction are reorganizing labor, sovereignty, and value creation. As before, elites seek coercive social control to manage upheaval.

New media and new industry are arriving together. When those forces combine, states tend to reach for familiar tools. Surveillance replaces overseers. Algorithms replace ledgers. Detention replaces plantations. The underlying logic remains: discipline surplus populations, extract value, and suppress democratic challenge.

Metaphors are not neutral. They orient strategy. If the problem is framed as a replay of European fascism, the response tends toward symbolic opposition and moral alarm. If the problem is understood as an unresolved civil war rooted in slavery, the implications are more unsettling. It suggests that the conflict is institutional, structural, and long-running. It demands reckoning, not nostalgia. It forces confrontation with the economic and cultural systems that made domination normal in the first place.

Calling this moment “Jim Crow for all” is a recognition that the tools once used selectively are being generalized. Precarity, surveillance, restricted movement, and conditional rights are no longer confined to racialized groups alone, though they still fall hardest there. The system is upgrading.

History does not repeat, but it does accumulate. Understanding that accumulation clarifies the stakes. The task ahead is to finally resolve a war that was never finished, and to dismantle the political economy that survived it.