262: The Hidden Ideology of AI

Why Boosters and Doomsters Share the Same Dangerous Assumptions

The ugliest part of the AI debate rarely names itself, yet it does most of the work.

Beneath the shouting between boosters and doomers runs a shared moral framework that treats intelligence as destiny, cognition as hierarchy, and worth as something to be measured, ranked, and optimized. Strip away the branding and the panic, and what remains is a familiar story: some minds count more than others, and technology exists to sort them.

The industry boosters lean into this logic with alarming ease. Their vision of progress depends on benchmarking humans against machines, celebrating speed, scale, and output as the highest virtues. Work is valuable insofar as it can be optimized. Thought matters insofar as it resembles computation. When they claim that AI will “outperform” doctors, writers, teachers, or judges, they are not merely forecasting efficiency gains. They are redefining value around narrow, machine-friendly metrics that erase care, context, and relational intelligence. Human difference becomes technical debt. Those who do not fit the model are framed as inefficiencies to be managed or costs to be reduced.

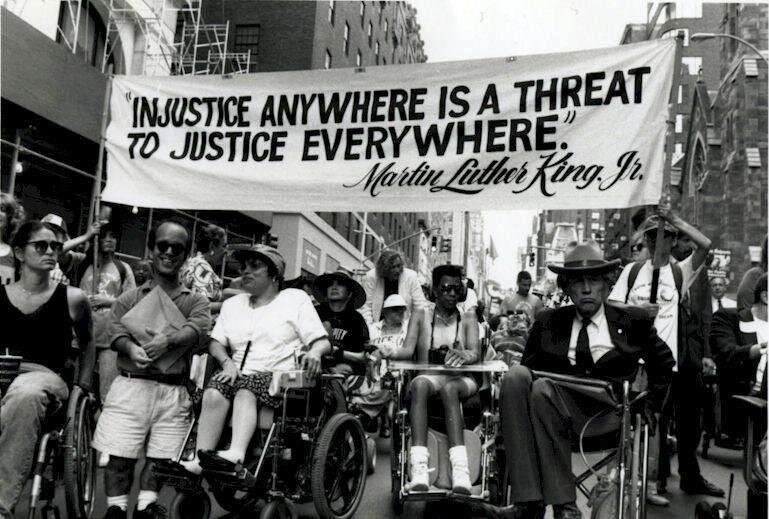

This worldview has consequences. It quietly legitimizes the idea that some people are surplus to requirement. That social participation must be earned through performance. That dignity follows productivity. These are not new ideas. They are industrial-era fantasies repackaged in neural-network jargon, and they echo older eugenic dreams of a society purified through measurement, exclusion, and control.

The doomers, despite positioning themselves as critics, often reinforce the same hierarchy from the opposite direction. Their arguments hinge on preserving a sacred image of human intelligence: unique, irreplaceable, and under threat. Creativity is treated as a fixed essence rather than a practice. Cognition is framed as singular rather than plural. The fear is not simply that machines will be misused, but that the boundary between “real” intelligence and other forms might blur. In that anxiety lies an unspoken premise: that intelligence must be protected from dilution, that its definition must be policed.

Here too, ableism does much of the work. Intelligence is imagined as fluent speech, rapid abstraction, and symbolic manipulation. Other forms of knowing—embodied, emotional, relational, nonverbal—are sidelined or ignored. Neurodivergence becomes an inconvenience to theory. Disability becomes invisible unless it can be instrumentalized as a cautionary tale. The critique claims to defend humanity while quietly narrowing who qualifies.

What unites these positions is not their stance on AI, but their agreement about value. Both sides accept a world in which minds are ranked, difference is suspect, and legitimacy flows from cognitive performance. Both struggle to imagine a society organized around care rather than competition, interdependence rather than optimization.

This shared foundation explains why the debate feels so sterile. It cannot produce wisdom because it begins from exclusion. It cannot address fascism because it reproduces the same logics of sorting and supremacy that authoritarian movements depend on. Fascism thrives on hierarchies of worth, on myths of strength and weakness, on the promise that complex social failures can be solved by identifying and removing the “unfit.” Any politics that treats intelligence as destiny, even inadvertently, leaves the door open.

An alternative begins elsewhere. Not with intelligence, but with care. Not with performance, but with relationship. Care recognizes that human capacity is uneven, contextual, and dynamic. It treats dependency as a universal condition rather than a personal failure. It values systems that support people where they are, rather than demanding that people conform to abstract ideals of efficiency or excellence.

From this perspective, AI stops being a rival or a threat to human worth. It becomes a tool whose legitimacy depends on whether it expands our capacity to care for one another and the planet. Does it reduce administrative burden in healthcare so practitioners can spend more time with patients? Does it help communities anticipate climate risks and coordinate mutual aid? Does it support accessibility, communication, and inclusion for people whose needs have long been ignored by institutions?

An ethic of empathy shifts the question from “What can this system replace?” to “Who does this help, and at what cost?” It demands governance structures that prioritize participation, consent, and accountability. It insists on literacy over hype, solidarity over spectacle, and pluralism over ranking.

When the AI bubble bursts, it will leave behind more than disappointed investors and obsolete slogans. It will expose the moral assumptions that animated the debate all along.

The choice that follows is not between machines and humans, or optimism and fear. It is between a politics of sorting and a politics of care.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser