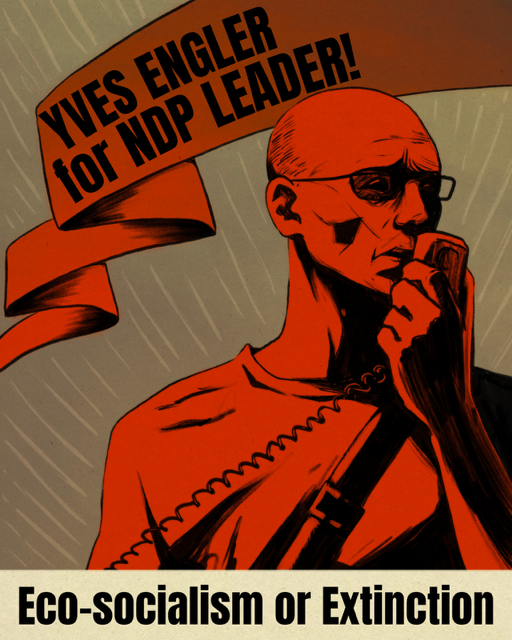

250: The Curious Case of Yves Engler

And The Inherent Insularity of Party Politics

Some leadership campaigns illuminate the character of a candidate. Others expose the structure of a system. Yves Engler’s attempt to lead the federal NDP does both. It forces us to confront what political parties have become, what activists imagine politics to be, and what authority now requires in an era where moral clarity and institutional power rarely intersect.

Engler is not running to make a point. He is running to win. He has been raising funds, organizing, testing messages, and building capacity for months. His ambition is real, and his critique of the party is not a pose. It is the backbone of a campaign designed to show that the NDP has lost contact with its movement roots and drifted into a defensive, managerial posture.

That seriousness sharpens the stakes. What happens when someone forged in activist confrontation attempts to cross the threshold from outsider to leader? What does it mean to seek authority within a structure one has spent years exposing and condemning? And can a political party still accommodate dissent deep enough to challenge its own identity?

We may not get answers to these questions as a consequence of Engler’s decision to submit his leadership application late in the vetting process. Critics framed this as disorganization, but that misreads the campaign entirely. Engler was not unprepared; he was already campaigning. The delay was intentional. By entering late, he ensured attention focused on the vetting itself—an arena where the party’s anxieties about internal democracy, ideological heterodoxy, and foreign-policy dissent become most visible.

But this strategy carried one significant cost.

By delaying formal entry, Engler missed the French-language debates, where he would have been the only truly bilingual candidate.

That stage was uniquely suited to his strengths. He could have demonstrated fluency, range, and confidence in a way none of his competitors could match. In a subdued leadership field, he could have reshaped the early narrative in a single evening.

Instead, he forfeited an arena where he held structural advantage.

If the objective is to win, not merely disrupt, this was the campaign’s first real strategic error. It did not slow his organizing, but it narrowed the pathways through which he could introduce himself to the membership and display contrast with the field.

Engler’s political identity was built through confrontation: challenging ministers at public events, exposing Canada’s role in global injustice, writing sharply against foreign-policy orthodoxy, and deploying shame as a tool to force recognition. This has moral potency. It has clarity. It generates attention.

But it does not build coalitions.

Activists—and journalists—often imagine themselves as occupying a distinct moral height. From that vantage, they believe they see more clearly, speak more honestly, and suffer fewer compromises than those inside institutions. But this stance, while flattering, is strategically suffocating. It presumes virtue instead of earning trust. It substitutes moral asymmetry for political connection.

And most importantly: shame is not a strategy for transformation. It is an accelerant for resentment. It hardens the very structures one seeks to open. It elevates the shamer while diminishing the possibility of alliance.

If Engler wants to win, he must pivot from moral distance to political intimacy. From indictment to persuasion. From performing rupture to cultivating reciprocity.

Leadership in a party is not granted to those who stand apart, but to those who can connect across disagreement. Authority is relational. It is slow. It is unglamorous. It demands sitting with people whose positions you find inadequate—not to shame them, but to understand how to move them.

Engler’s candidacy hits the NDP where it is most fragile. The party’s movement DNA has thinned. Its foreign-policy positions track caution more than conviction. Its activist base is increasingly alienated. Its internal processes seem designed to manage dissent, not channel it.

Engler recognizes this. His campaign is a pressure test for the party’s identity: can it still host real ideological struggle, or has it become a parliamentary shell optimized for predictability?

By delaying his entry, Engler forced attention onto the vetting process—the soft underbelly of party democracy. By missing the French debate, he lost an opportunity to change the race. The tension between these choices reveals a campaign that is simultaneously strategic and fallible: sharp in diagnosis, but imperfect in execution.

Engler’s leadership bid revives an old philosophical question that contemporary politics keeps trying to ignore: is politics a cooperative endeavour or a contest of will?

If politics requires cooperation, then Engler’s activist posture becomes a liability. He must demonstrate he can work with people he spent years confronting.

If politics is contestation, then his clarity, courage, and willingness to expose contradictions become a competitive advantage.

But the truth is that politics is both. It requires the ability to confront and the patience to collaborate. Authority today is not earned through purity but through coherence: the ability to connect critique to capacity, dissent to durability.

The activist who wants to win must learn to build, not just break. They must understand that moral clarity is only one ingredient of political power—and often not the most important.

The Curious Case of Yves Engler tells us something urgent about Canadian politics and the contemporary left:

Parties have lost their monopoly on political legitimacy.

Activists must rethink moral exceptionalism.

Authority emerges through connection, not condemnation.

Internal democracy only matters if parties tolerate genuine dissent.

A single missed debate can matter more than a year of organizing, because authority is performed, not presumed.

Engler’s campaign is not merely a challenge to the NDP. It is a challenge to the idea that politics can be transformed from the outside without learning how to inhabit the inside. It tests whether someone who built influence through exposure can convert it into leadership through persuasion.

Whether he wins is almost secondary. What matters is the question his campaign forces us to confront: can contemporary political parties still accommodate transformative ambition? And can activists seeking power learn to build the relational structures that power requires?

Here at Metaviews, we still see the NDP in the past:

Whether the Party has a future, or a living one, rather than a zombified one, will depend on how this leadership race unfolds.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser