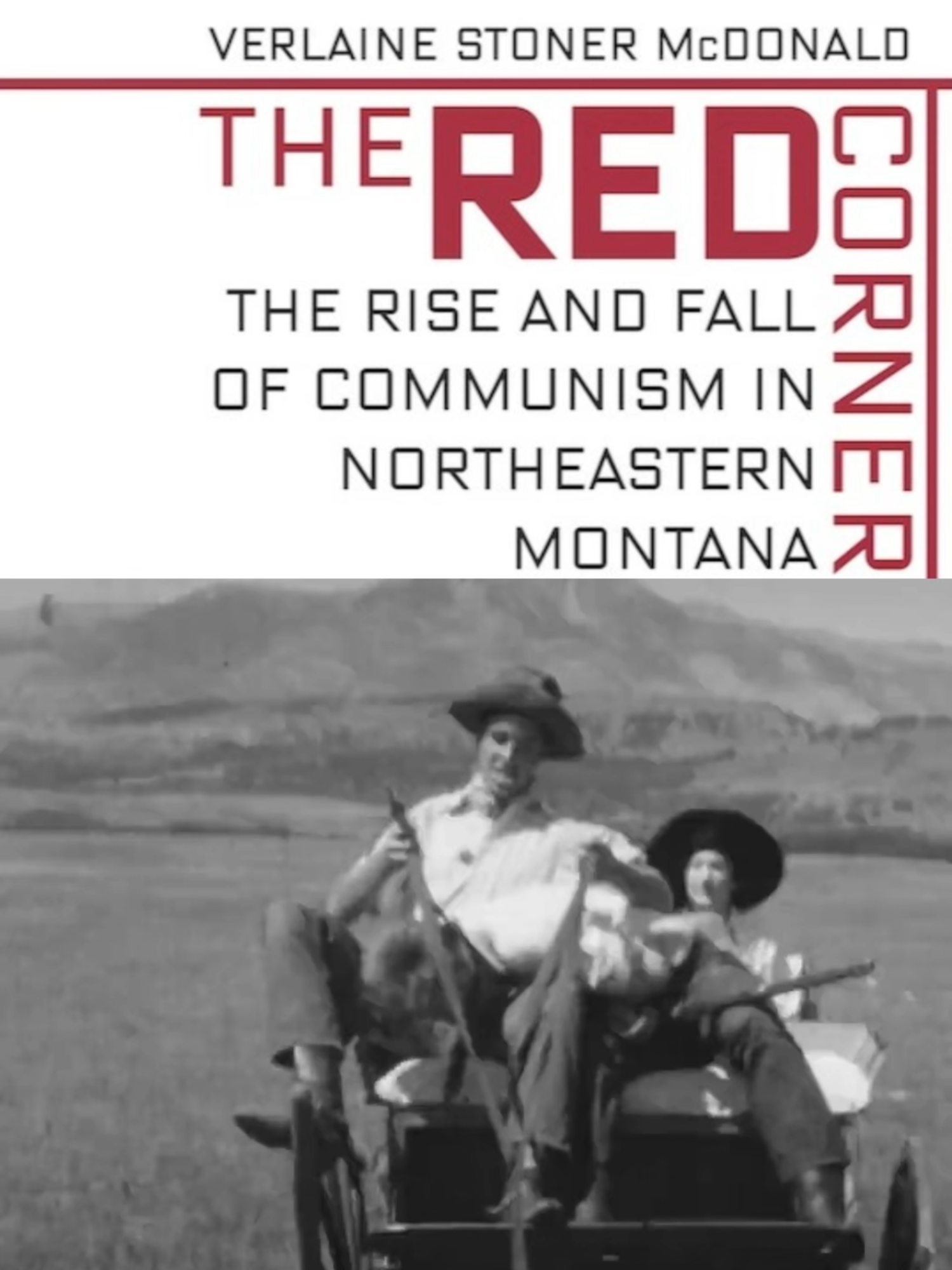

162: The Red Corner: Montana's Forgotten Revolution

The Revolution Grew in the Fields. Then They Buried It.

In the windswept prairies of northeastern Montana, a radical experiment in political power once bloomed. Sheridan County, now a deep-red bastion of rural conservatism, was once known as "The Red Corner," a nickname born not from Republican allegiance but from its embrace of socialism and communism in the early 20th century. This forgotten chapter in American history is more than a curiosity—it is a reminder that even in the most unlikely places, revolutionary politics can take root, and liberalism can be rejected not only from the right, but also from the left.

Today, Montana finds itself again at the center of a political identity crisis. Its mythology of rugged individualism has long been co-opted by neoliberal ideology, yet the material reality is one of poverty, ecological crisis, and state neglect. The political choices available to Montanans are often framed as a binary between libertarian conservatism and corporate liberalism—a false dichotomy that leaves many disillusioned. This disillusionment once gave rise to the Red Corner. It could again.

What Was the Red Corner?

In the 1920s and 30s, Sheridan County became a hotbed for radical organizing. Charles E. Taylor, a firebrand editor and organizer, turned The Producers News into a mouthpiece for socialism and later communism, advocating for the rights of farmers crushed under debt, monopolies, and failed government policies. The Nonpartisan League and Communist Party both gained traction, and local officials openly ran on platforms of economic justice and collective ownership.

This was not utopia. It was political resistance built from necessity. Farmers who had been promised prosperity by the liberal capitalist system found themselves abandoned. The Red Corner offered them solidarity and a critique of the liberal order that had failed them. Through cooperatives, union organizing, and democratic control of local governance, they forged an alternative.

The Red Corner’s story complicates the usual American narrative in which liberal democracy is portrayed as the middle road between authoritarianism and chaos. Instead, it illustrates that liberalism itself can be a source of abandonment and betrayal. The farmers of Sheridan County did not turn to radical politics because they hated democracy. They did so because liberal democracy had ceased to function for them. It privileged urban elites, corporate monopolies, and a federal government that treated the rural poor as disposable.

That same structural critique remains valid today. Modern liberalism, often synonymous with technocratic governance and market fundamentalism, has gutted public services, depoliticized collective action, and reduced politics to branding. It leaves people with few real options and then chastises them for seeking alternatives.

Contemporary Montana is shaped by these same forces of exclusion and frustration. Conservative populism has filled the void, offering cultural identity and grievance politics where liberalism offered only managed decline. But the soil remains fertile for a different kind of resistance—a reawakening of cooperative institutions, mutual aid, and political imagination grounded in place-based solidarity.

The Red Corner was never about ideology alone. It was about agency, dignity, and survival. If it happened once, it can happen again. We must learn from this legacy, not as nostalgia, but as a blueprint.

The Red Corner reminds us that liberalism is not the default, nor is it inevitable. It is a framework that must be earned, and when it fails, it will be replaced. The question is: by what?

If we want to build a future of authority rooted in justice, we must look to the past not as a museum, but as a map.

Revolution grows in the cracks of failed systems. Montana has seen it before. It might again.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser