Towards An Ethics of Immortality

Technology and ethics are strange bedfellows.

Technology and ethics are strange bedfellows.

Once we have a tool, it becomes really difficult to not use it.

How we use it and why we use it are key ethical questions.

Every tool shapes the task, and if you’ve got a hammer, you’re bound to look for nails.

Health technology is a great example of this, as it not only transforms how we care for ourselves, but also how we understand ourselves, and how we relate to others.

Without irony, there are some really rich people and some really smart people who are collaborating on the technology of immortality.

Seem absurd? Tools to help us live forever? Delusional dreams of divinity?

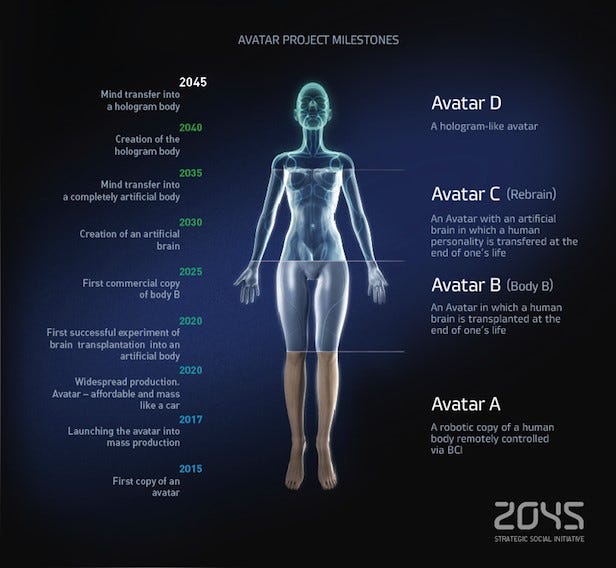

These are largely products of the cult of singularity. The shared hallucination that humans are machines, with computers as brains, and sometime soon we’ll build external machines and powerful computers that we can transfer to, and live forever.

However we are not computers. We cannot be uploaded. We will die. This I do believe.

Yet there will be powerful side effects and consequences from the pursuit of immortality.

Some of us will live a whole lot longer than we planned, maybe even than we desired.

Rather than immortality, what we’ll probably end up with are tools towards longevity.

Should we be regulating and monitoring how these tools are developed and used? Or should we just blindly embrace the pursuit itself? Or both. At least let us talk about it, asking questions about how these tools could be used and why.

For example, do your retirement plans include a contingency for multiple decades of unexpected lifespan?

Do you want to lead a long life, if that life is spent sick and miserable with limited mobility?

How we perceive retirement will certainly change, but what about work itself? Would you work harder if you knew you had to work longer?

The healthcare sector is already being transformed by the prospect of increased longevity, but what about insurance? Should insurance be cheaper if you end up paying for it longer?

What about real estate? Do longer mortgages become more appealing or does home ownership have less appeal as we desire to move around as we age?

Increased longevity will have an impact on all aspects of our lives, especially our values, and our broader society, as our relationship with time becomes less urgent and seemingly scarce?

Or alternatively, what kind of society would result if those with the greatest amount of wealth were able to live significantly longer than those without wealth? Given that this is already the case, an obvious answer would be an increasingly polarized society where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer and die younger.

My brother Jacob Hirsh adds:

“Small longevity extensions at the end of life already eat up a disproportionate share of the overstrained health care budget. What will happen when older (and wealthier, more politically influential) people demand even more resources to sustain their lives further? The needs of younger people (especially children) will inevitably be devalued in comparison. Even if the technologies themselves are relatively cheap, extensions of longevity will increase inequality by limiting resource availability for younger people (nothing left to inherit from the previous generation of rulers).”

Yet what if death is not an option, or at least not something that comes when you want it to?

What if a person of a late age commits a crime and are sentenced to a term that is clearly longer than they will live. Will they be subject to non-consensual life extension to ensure that they serve their sentence?

Will longevity only be accessible to the rich? What if it were imposed upon the working poor?

What if you could live to 200 but only if you agreed to live an additional 500 years in a jar? Would you, given that you don’t know what it’s like to live in a jar?

Here’s something to remember when thinking about the future.

As far as our experience as humans, there is no future, only the present, and maybe some of the past. The longer we live, the more presents we experience but do we accumulate more past? What if the past is just a memory we reconstruct when remembering?

How can we plan for the future when all we know is the past and the present?

We live in a tyranny of “todays”, as our relationship with space and time means that we can only ever experience today. Carpe diem (a/k/a YOLO).

Yet we cannot escape the future either. It will always be there. Looming. Producing an endless source of “todays” for us to experience. The choices we make and the actions we take today directly impact the future, and whatever “todays” that future presents.

We experience time as we do because of our bodies. They are the vessels that carry us forward through time in space. This is partly why we’re not machines and our brains cannot be uploaded to a computer.

Our intelligence is embodied. Our bodies are our brains. Our muscles contain memories. Our senses trigger scenes from our past and instinctual responses. Our guts are a central part of our consciousness.

What if we’re not a single sentient organism but a federation of living beings united by space and time where consciousness is the parliament in which we debate our actions and state of being?

Jacob offers some further reflection:

“There are also lots of interesting ethical questions when you take the possibility of uploading consciousness seriously. We currently view human life as being intrinsically valuable, for religious and evolutionary reasons. But really, we are talking about human minds (or souls) as being intrinsically valuable. If the mind can be transferred to a different material substrate, does it still have intrinsic value? Must it be preserved in its current form at all costs? Is self-archiving (making backups of one’s consciousness at different points in development) necessary to preserve this value? When should the mind be allowed or prevented from changing (i.e., being integrated into a larger network of minds and computers)? If ending a life is the greatest moral violation imaginable, does this apply to ending a digitized mind as well? If not, then why not? In principle, it is the subjective consciousness of minds that gives them their intrinsic value, not the bodies that they happen to inhabit.

It’s also not clear how to engage with these ethical questions. An intuitionist approach would suggest that we should go with our feelings about right and wrong. But these feelings are based on our evolutionary history and can lead to extreme prejudice against anyone who is not our kin. A utilitarian approach would suggest that we balance the costs and benefits of immortality, which would mean keeping people alive as long as they contribute to the economy at a higher rate than their medical costs (i.e., the net impact of an individual life on collective well-being). But this eliminates any concern for the intrinsic value of (human) life. A principled approach would begin with the assumption that human life has intrinsic value, but this value must ultimately be quantified in order for practical economic decisions to be made, and it’s not clear how this principle would operate in a transhuman context (as per paragraph above).

If anything, dramatic advances in health-related technology expose the many contradictions in our ethics. At some point, the medical goal of preserving the life of a focal individual could lead to disastrous consequences for the collective (i.e., the ecology of beings that make life possible for anyone).”